A meeting I facilitated a couple of weeks ago got me thinking a lot about test length. How long should a test be? How many items? How many hours?

Perceptions

What struck me during the meeting was the importance of the perception that the test is rigorous. We can talk about measurement considerations all we want; if the person who would hire a certificant thinks the certification is too easy to attain, the credential will have little value.

Say a credential has a five-hour test with 200 multiple-choice items. A new credential in the same field with a two-hour multiple-choice test will be perceived as less credible. The perception could be overcome, in part, by offering a different kind of test: a performance test, for example. But the fact remains that perception is an important part of the decision about test length.

Say a credential has a five-hour test with 200 multiple-choice items. A new credential in the same field with a two-hour multiple-choice test will be perceived as less credible. The perception could be overcome, in part, by offering a different kind of test: a performance test, for example. But the fact remains that perception is an important part of the decision about test length.

Presumably, the pressure goes in the opposite direction as well. If an advanced credential has a two-hour test, it may be hard to market an entry-level credential in the same field with a three-hour test.

On occasion, we include a question about test length in the JTA validation survey. It is a good way of finding out perceptions of what passes in the profession as stringent enough.

Cost and Complexity

The other considerations in determining test length are cost and complexity.

Exam seat time costs money. Item development requires resources. You want the shortest test that will do the job reliably. In certification, “the job” is to make a pass-fail decision that grants certification to every applicant who can demonstrate that he or she deserves it, and withholds certification from everyone else.

A secondary part of “the job” of a certification exam is to guide failing candidates in preparing for a retake. If you consider this feedback to be important, then you need a test long enough to provide reliable information about candidate performance in your smallest content domains.

Content domains really matter. Often, in professions, some people are really good at Thing 1 and Thing 2 but spend very little time on Thing 3. Others are amazing at Thing 3 and spend little time on other Things. By basing pass-fail decisions on the total score, you allow expertise in one domain to compensate for gaps in another domain. That’s good. But traditional measures of test reliability, like Cronbach’s alpha, reward tests where doing well on Thing 1 is predictive of doing well on Thing 2 and all Things, and doing poorly on Thing 1 is predictive of doing poorly across the board.

Content domains really matter. Often, in professions, some people are really good at Thing 1 and Thing 2 but spend very little time on Thing 3. Others are amazing at Thing 3 and spend little time on other Things. By basing pass-fail decisions on the total score, you allow expertise in one domain to compensate for gaps in another domain. That’s good. But traditional measures of test reliability, like Cronbach’s alpha, reward tests where doing well on Thing 1 is predictive of doing well on Thing 2 and all Things, and doing poorly on Thing 1 is predictive of doing poorly across the board.

If performance on one domain isn’t expected to predict overall performance very well, you need a longer test to achieve good reliability parameters.

How long is long enough?

Take a 100-item test and add 100 similar items. You will have a more reliable test.

Take the same 100-item test and remove the 20 poorest-performing items. Again, you will almost certainly have a more reliable test.

Of course, if you achieve greater reliability by eliminating poor items, you still need a pipeline of excellent items for future iterations.

In short, quantity of items matters, but quality rules.

You don’t know the quality of your item pool in advance, so where do you start?

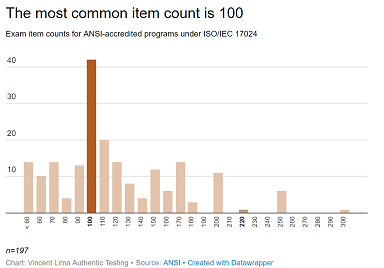

Survey of Tests for ANSI-Accredited Programs

To explore best practices in certification, I looked at specifications for every test offered by bodies accredited by the American National Standards Institute for conformity with ISO/IEC 17024, “General requirements for bodies operating certification of persons.” At the time of this writing, there were 67 accredited certification bodies operating 198 programs.

Almost all the programs involved multiple-choice tests. Some included performance tests alongside the multiple-choice exams. Other involved simulations alongside the multiple-choice items.

Longest tests. The American Institute of Constructors had an Associate Constructor program with a 300-item test. This was the biggest item count among the tests associated with ANSI-accredited programs. At eight hours, it was tied with one other test for longest exam: the 160-item test for the Qualified Elevator Inspector (QEI) credential offered by (our client) NAESA International.

Fewest items. The Personal Financial Planner (PFP) credential offered by the Canadian Securities Institute required two tests. One of them had eight to 12 case studies, but these case studies were said to often have “sub-questions,” and the test allowed 3 hours, so it’s not exactly a short test.

For the Lift Director certification offered by (our client) the National Commission for Certification of Crane Operators, a candidate had to pass a core test, a specialty exam, and a performance test. The Mobile Cranes Specialty Exam contained 15 items, to be completed in 120 minutes. The Tower Cranes Specialty Exam also contained 15 items, to be completed in 60 minutes.

In short, the shortest tests are generally part of a battery of tests required for a credential.

Least time. The Crane Operators had some other one-hour tests. Also coming in at one hour was the test for the Cisco Cyber Security Specialist Program.

Central tendency. The mean item count was 119. The median item count was 110. Fully 42 tests had exactly 100 items; that was the most common item count.

The mean seat time was 168 minutes, or almost 3 hours. The median time was 150 minutes or 2½ hours. Fully 41 tests allowed 3 hours of seat time; that was the most common seat time.

So how long should your test be? I’d start with a 100-item test (of which 20 are unscored) and two hours. I’d then consider, based on the factors discussed above, whether more items and time are needed.